Militant Ironies:

Art as a Strategic Weapon in Israel’s Culture Wars

TEXT / PIL AND GALIA KOLLECTIV

view of the exhibition Mini Israel: 70 Models, 45 Artists, One Space at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem

Looking at Israel from without, it’s easy to get lost in the big picture, boiling the country down to a two-sided conflict between Arabs and Jews. From within, one gets too caught up in the detail, too embroiled in the numerous sects and particular interests that make Israeli culture a cacophony of conflicts, which the Arab/Jewish struggle can barely keep in check. Titled after a model theme park featuring an idealized Israel, Larry Abramson’s exhibition Mini Israel: 70 Models, 45 Artists, One Space rightly defines the problem as an issue of scale. Presenting seventy artists’ scale models of various aspects of Israeli society in The Israel Museum in Jerusalem, he has created an overview that aims to provide the critical distance so lacking in this fraught society. Having lived away from it all for most of the last six years, we still feel sensitive to some subtleties. At the same time, we are keenly aware of shifts in the political discourse that our friends back home seem to take for granted: curious euphemisms—like “disengagement” and “compensated evacuation”—litter a mutating political landscape. This shifting terrain is itself a representation of the struggle to come to terms with the idea of getting out of the occupied territories—once a radical left heresy and now almost a consensus view. Words like “transfer” have traversed the political spectrum, and are now being applied to the treatment of settlers instead of being shorthand for a proposal for the disposal of the Palestinian population. We are not quite sure what scale we occupy, but disorientation, as Abramson appears to be suggesting, is a good place to start.

Partial view of the exhibition Disengagement (courtesy of the artists and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art)

An exhibition entitled Disengagement at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art explores the dismantling of the Gaza strip settlements, supposedly from all sides. For the first time in many years, right-wing art shares a platform with the left’s more predictable oppositions, in videos affording the settlers center stage and allowing them to compare their woes to those of the holocaust’s victims, and in painterly portrayals of their pained compromises. As a result, both positions are blurred into a sentimental tragedy with no agency—while Palestinian responses are conspicuously absent. The attempt to make an ultimately negligible part of the occupation’s ongoing saga so central falls flat in the face of the theatricality of the disengagement itself, rehearsed like a high school play between soldiers and settlers to the point where artistic commentary had become superfluous. David Ratner of Haaretz newspaper has been quoted by The Guardian’s Rachel Shabi as saying

They held meetings where the settlers would say, “Let's keep to the agreement, we don't beat up the soldiers, we will lie on the ground holding hands,” and the soldiers were saying, “We will break you apart, in small squads of four soldiers but not using excessive force, and you are not allowed to kick at the military.”1

Partial view of the exhibition Disengagement (courtesy of the artists and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art)

As Ziv Koren’s journalistic photos of the army’s manoeuvres illustrate, there is enough high drama in the reality of the evacuation without the ideologically motivated compositions of the more artistic representations on show.

Ziv Koren, “Massada” unit’s training for the pullout from Gush Katif, July 2005, 2005, Lambda print, 70 X 100 cm, featured in the exhibition Disengagement at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (courtesy of the artist and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art)

In a recent book, Graciela Trajtenberg, claims that the Israeli art world was formed as an autonomous field, positing art for art’s sake in distinction from an otherwise politically engaged Israeli society.2 Whether or not Trajtenberg is correct in setting up early attempts at European abstraction and aestheticism as apolitical, the immediate political concerns of the region have since come to dominate artistic production, establishing a kind of state of emergency for the arts that parallels that of the entire country. As Ronen Eidelman and Yael Barda write in the current issue of Ma’arav, an online art and culture magazine,

Israeli art, much like the Israeli peace industry, has turned protest into a profession. The critical artist opposes the occupation and the exploitation, goes to biennials, exhibits in shows, travels the world and receives approbation and recognition for his mere acknowledgement of the situation (at best documenting those struggling to change it).3

In other words, political art in Israel functions much like the work of a disillusioned activist of the “Women for Human Rights” group who, standing in army posts in the occupied territories, keeping a watchful eye on the way IDF [Israel Defense Forces] soldiers treat the civilian population, described her impact: “you become part of the army post, a cog in the machine, and both sides—the soldiers and the Palestinian—simply take your presence there for granted, a constant silent witness.”

But, while art has been swallowed up by this impotent political discourse, it is hard to shrug off a creeping sensation that it—and, particularly, the radical aspects of the avant-garde tradition—has also been absorbed into the political center without seriously changing its structures, hegemonies, and injustices. In Israel, politics almost functions as artistic critique: the results of this year’s elections were deeply influenced by a popular television satire show and the negligible pensioners party won an impressive seven seats in the parliament largely because many young voters, in an act of political defiance and sheer irony, decided such a vote would somehow reflect the absurdity of the political situation. This is a nightmarish version of the 1968 generation’s old dream: a collapse of the distinction between life and art, creating an open, free space where play and work are united. Writing in the May issue of Frieze, Eyal Weizman described the Israeli army’s adoption of the theories of Deleuze, Foucault, and Debord, as well as a host of architectural theorists, in developing new approaches to urban warfare.4 Deleuze and Guattari’s ideas about decentralisation, swarm intelligence, and smooth space, Debord’s dérive and détournement as subversive interpretations of space, and Tschumi’s writing against the rationalism of the postwar architectural strait jacket have allowed the IDF “war machine” to transcend the “state apparatus” and its “striations,” moving through walls instead of alleys and reconfiguring living spaces as battle stations.

Jakup Ferri, still from Save Me, Help Me, 2003, video, 10:24 minutes, featured in the exhibition This is not America (courtesy of the artist and ByArts Project Gallery, Tel Aviv)

A mere forty-five minute drive—if traffic isn’t too bad—separates Jerusalem, the nominal capital, from Tel Aviv, Israel’s cultural center. Yet, the divide between the two is as stark as it has ever been. A vibrant art scene thrives in Tel Aviv’s commercial galleries, while art in the holy city, although home to the country’s foremost art school, has until recently been limited to a handful of state-funded institutions like The Israel Museum—whose focus is as much archaeological as it is artistic—and a small strip of downtown Judaica merchants.

Erkan Özgen and Sener Özmen, still from The Road to Tate Modern, 2003, video, 6:26 minutes, 3/6 edition + 1AP, featured in the exhibition This is not America (courtesy of the artist and ByArts Project Gallery, Tel Aviv)

Straddling local and international concerns and aesthetics, the Tel Aviv art scene boasts exhibitions by expats made good like Guy Ben-Ner and Michal Rovner, alongside other imports and exports. This is not America, an exhibition curated by Galit Eilat and presented at ByArts Project Gallery, enlists the work of Balkan artists to illustrate the dilemmas that the periphery faces when it seeks to develop its own representation. Short sketches about globalization by the Siberian Blue Noses Group accompany Kosovan Jakup Ferri’s pathetic plea to a curator in the video Save Me, Help Me, 2003, listing ideas for work he could make to appeal to the international art market, and Erkan Özgen and Sener Özmen’s The Road to Tate Modern, 2003, a Quixotian quest for the west across the dry mountains of Turkey. Somehow, this show of foreign art manages to say more about the local conditions of art making and the impact of the political on the aesthetic than either of the major museum shows that address the situation more directly. At the same time, it is too easy to discuss the marginalization of the periphery from within the enclave of cosmopolitanism that is the Tel Aviv art scene. Nowhere would an exhibition like this be more pertinent than in the state capital.

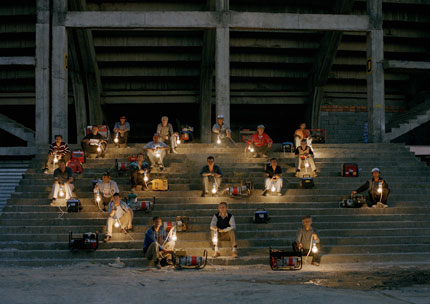

Adrian Paci, Turn On, 2003, video, 4 minutes, featured in the exhibition This is not America (courtesy of the artist and ByArts Project Gallery, Tel Aviv)

In Jerusalem, meanwhile, postmodern (anti)narratives become pure utopian fantasies. Much as we would like to see cities as free flowing socio-geographic bodies in a constant state of flux, where solids melt into air under the feet of casual flâneurs following the new IDF paradigms identified by Weizman, Jerusalem will not abide. Many obstacles, physical and cultural, delineate the city’s social space. The city’s genealogy—violent cycles of conquest and liberation from King David, the Crusades, Saladin, the Turks, and the British mandate to Zionism—is so present that, for many Israelis, the “heart of the city is the ancient holy wall,” a line from a post 1967 patriotic song which is still widely popular. Cutting across the city and separating the eastern Palestinian side from the Jewish one to the west, the Ottoman wall is perhaps the most visible of these obstacles. But Jerusalem is also rigidly divided into ethnically and culturally homogenous neighbourhoods: poor ultra-orthodox Ashkenazi neighbourhoods; ugly settlement-suburbs on the desert’s edge, roughly divided between new immigrants from Russia and older ones from North African countries; richer quiet neighbourhoods in the west; and a few Palestinian villages scattered among them. On Saturday afternoons, police barriers block car entrance to the ultra-religious neighbourhoods where stoning is almost inevitable if one nevertheless dares to cross.

In the midst of all this, art is being strategically used by the city council and other governmental organisations to rejuvenate the dying city center, which has long been replaced by a chain of suburban malls as the main shopping and entertainment destination—a mirror image of the atomization of the local scene and of Israeli society in general. A few artist-run galleries have, for the first time in many years, popped up in the trendier area behind the busy Ben-Yehuda market. The city council financially assists some of them, such as Barbur. Agripas 12 is managed by a group of twelve artists who share the rent while another, Al-Hoash, lies in the city’s eastern side, behind the wall.

Yoav Weiss, Surveillance Plane, 2005, steel, paper, video camera, 70 x 200 x 200 cm, featured in the exhibition Mini Israel: 70 Models, 45 Artists, One Space (collection of the artist; courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

Over the last decade, property prices have dropped rapidly in Jerusalem because of the Intifada. The city council now wants to create an arty buzz to raise the prices again, and although some of these artistic initiatives are quite brave, the art suffers as a result of its complicity with this planned gentrification—or so we are told by the proudly independent Jerusalem artists’ group Sala-Manca. Activity for its own sake can prevent the development of interesting art while an exciting new spirit of entrepreneurship often obscures both the limitations of the local art scene and its instrumentalization by official organisations. In many ways, cultural entrepreneurship is just another weapon in the postmodern arsenal, another step in the cycle of conquests that has defined and reinvented Jerusalem over the centuries. The most startling example of a misguided—and perhaps even cynical—exploitation of culture in the new gentrified Jerusalem is the recent proposal to build a Museum of Tolerance on the site of the centuries-old Muslim cemetery. If Jerusalem has been the symbol of various religious utopias throughout history, the proposed museum seems to carry it into the utopian discourse of the present—neo-liberalism—replacing the real city with an imaginary, politically correct idea of an end to conflict.

Maayan Strauss, Settlement Evacuation, 2002, Playmobil pieces, sand, stones, 50 x 120 x 120 cm, featured in the exhibition Mini Israel: 70 Models, 45 Artists, One Space at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (collection of the artist)

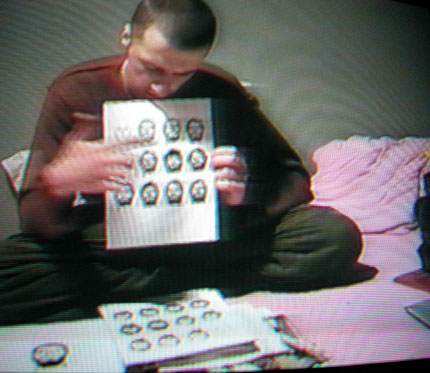

A few months ago, plans were announced to relocate the Bezal’el Academy of Art and Design from its gritty mountaintop building, overlooking the Palestinian village of Isawiya in the north, to the center. Prof. Arnon Zuckerman, the academy’s president, insists that an art school needs to be in a living, organic site and not an isolated location. At the same time, Bezal’el’s degree show has been controversially transferred to the old airport in Lod, a move described by art critic Yonatan Amir as an attempt to escape the Levant, subsuming the local in the echoes of propeller noise still connecting Jerusalem to foreign dreams.5 Walking through the exhibition Mini Israel, where miniature surveillance planes hover over miniature bomb explosions moored next to miniature concrete skyscrapers and a hollowed out mini-mosque, one is subjected to the double scope of Israeli art, which no foreign dream can seduce to unity. The world outside the museum is ever present, not just referenced but physically scaled down. Several artists have made use of Lego style toys and dolls in their work. Nevertheless, curator Abramson claims that Mini Israel’s compromised playful position has reintroduced a sense of social responsibility to art in the wake of its failure to find meaning in the everyday. Judged against the simulations of the political arena in general, and the IDF in particular, re-enacting the occupation as child’s play hardly feels subversive or critical. The pleasure of finding new art and creative energy in Jerusalem is marred by the sense that, as with Baudrillard’s Disneyland, the borders of the theme park that is the Zionist project have been eroded.

NOTES

1. Rachel Shabi, “Making human drama out of a political crisis,” The Guardian, January 9, 2006, http://www.guardian.co.uk/israel/Story/0,,1681960,00.html, accessed June 24, 2006

2. Graciela Trajtenberg, Between Nationalism and Art: The Construction of the Israeli Field of Art During the Yishuv Period and the State’s Early Years, Jerusalem: Magnes, 2005.

3. Ronen Eidelman and Yael Barda, “The Exceptional State of Art,” Ma’arav 4, June 6, 2006, http://maarav.org.il/classes/PUItem.php?id=751&lang=ENG, accessed June 24, 2006

4. Eyal Weizman, “The Art of War,” Frieze 99, May 2006, http://www.frieze.com/feature_single.asp?f=1165, accessed June 24, 2006.

5. Yonatan Amir, “Terminal, Je t’aime?,” Ha’Ir Magazine, June 14, 2006, http://www.notes.co.il/yonatan/19941.asp, accessed June 24, 2006.

Contributing Editors Pil and Galia Kollectiv are London-based artists, writers, and independent curators. They wrote this text in June 2006.